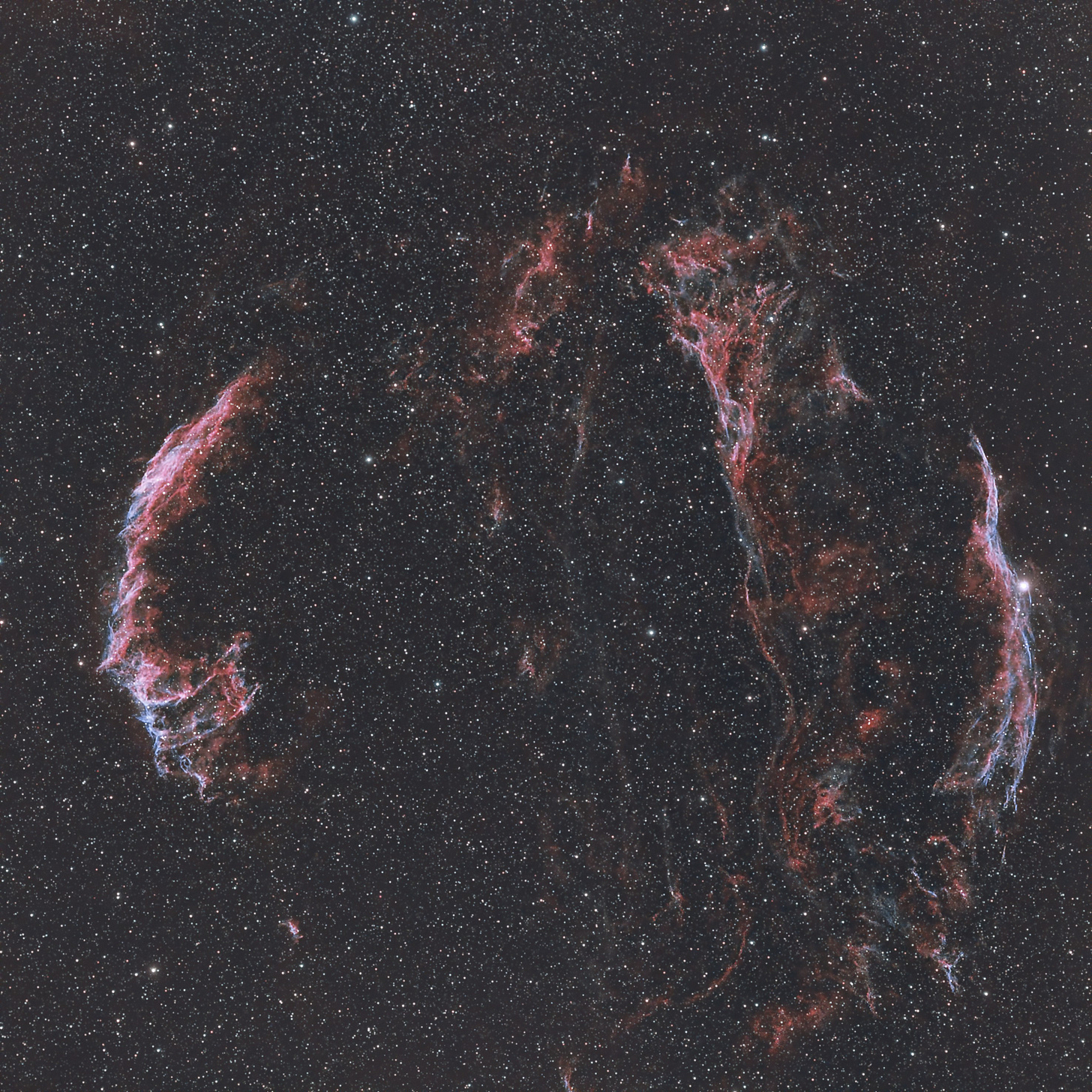

Tangled in the eastern ‘wing’ of the spectacular constellation Cygnus, the Swan, the delicate lacework of the Veil Nebula belies its origins in one of the most powerful explosions in the galaxy. This sprawling complex, just off the band of the summer Milky Way, spans the diameter of seven full moons and beguiles the observer with its complexity and ragged symmetry. It’s always worthy of a quick look and easily warrants an entire night at the telescope to see all of its rich and complex structure.

Once thought to be caused by two separate stellar detonations, the Veil Nebula, also known as the Cygnus Loop, was likely produced by a single star of about twenty solar masses that blew up as a supernova about 8,000 years ago. A supernova explosion occurs as big stars run out of fuel in their core and become unable to hold themselves up against the relentless pull of their own gravity. Their outer layers collapse, crush the star’s dense core into a neutron star or black hole, then snap back in a violent explosion that ejects as much energy in a few minutes as our sun does in its entire lifetime. At a distance of just 2,100 light years, the event must have been spectacularly bright and visible even by daylight for weeks to pre-historic stargazers, inciting much speculation about the nature of the night sky - a certainly a great deal of awe.

Upon detonation of the supernova, the shock wave expanded and smashed into an expanding bubble of gas cast off by the star before it exploded. The nebula now spans about 110 light years and it continues to expand at a rate of about 1.5 million kilometers per hour. Astronomers have directly observed the expansion of the nebula by comparing images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope between 1997 and 2015. We see nebulosity spread over about 3.5 degrees of sky or about the width of three fingers held at arm’s length.

Since only the largest stars expire like this, and since the explosion itself plays out quickly over a few days or weeks, a supernova is a relatively rare event: the last known supernova in the Milky Way happened more than 400 years ago. Such explosions often leave a long-lasting imprint in the form of a visible nebula caused by the rapidly expanding shock wave. Dozens of these so-called supernova remnants fleck the night sky with evocative names like the Spaghetti Nebula, the Jellyfish Nebula, and the Manatee nebula. Most require a substantial amateur telescope and sensitive camera to detect. But except for the much smaller Crab Nebula, the sprawling Cygnus Loop is one of the easiest to see and photograph and one of the most intricate and intrinsically beautiful objects in our galaxy.

While it’s lovely to behold the Veil Nebula in photos as a form of abstract sculpture on a galactic scale, it’s also an object you can see for yourself. The complex lies a few degrees off the star epsilon (ε) Cygni (Gienah) at the tip of the eastern wing of Cygnus. It’s easily within reach of a small telescope in dark sky, especially with the help of a nebula filter, and even in a good pair of 10x50 binoculars. Like many sights in the deep sky, the Veil was first glimpsed by William Herschel in 1784. He noticed the western end of the nebula, now cataloged as NGC 6960, which runs through the 4th-magnitude star 52 Cygni. The eastern arc of the Veil complex (NGC 6992 and NGC 6995) is easier to see in a telescope and arguably more intricate and appealing. Unless you have a field of view of 4o or more (a large field for a telescope), you’ll only see one section at a time. Even the brightest part of the Veil, NGC 6992, is roughly a full degree across. The delicate lacework becomes visible in 4” or larger telescopes with a UHC or OIII filter. Use higher magnification (and more aperture if possible) to see the finer structure.

Between the two elongated sections lies the more tenuous section called Pickering’s Triangle named after Harvard astronomer Edward Charles Pickering, although to me it looks in images more like an interstellar tornado. Pickering captured an image of this section, but it was first noticed by his redoubtable assistant, Williamina Fleming. A single mother with little formal education, Fleming served as a maid in Pickering’s home until his wife noticed her keen intellect and recommended her to her husband for a position at the Harvard College Observatory in 1879. She soon became a keen and prolific analyzer of stellar spectra and discovered the now-famous Horsehead Nebula in Orion, also on a photographic plate made by Pickering.

Without question, my best view of the Veil, or at least one small and intricately knotted section of the eastern Veil (NGC 6992), came on a clear July night in 2011 in the Adirondacks in New York State. The biggest scope at the observing site was a 25” Dobsonian with a stepladder leading up to the eyepiece, aimed at the Veil Nebula. There was no lineup to look through the scope, only one young woman descending the ladder after seeing the nebula and wondering what all the fuss was about. She was interested, but clearly a beginner and didn’t have much to compare it to. The owner of the telescope explained patiently that it was indeed an impressive sight and that a more experienced observer would find it so. I asked the owner if I could head up to take a look. As he continued his explanation to the young woman, I looked through the eyepiece. “Oh my GOD”, I said. “See”, said the telescope’s owner, nodding towards me at the top of the ladder. “He is an experienced observer”.

Given its size, relative brightness, and complex shape, the photogenic Cygnus Loop also makes an excellent target for astrophotography. I’ve captured simple images using nothing more than a small monochrome astro-camera perched stationary on a picnic table and pointed straight up when the Veil was nearly overhead. A little more effort and gear yield spectacular results. All the images on this page were made with a modest astronomy camera and various camera lenses with less than one inch aperture (and a little practice). Of course, the Hubble Space Telescope takes pretty good pictures of the Veil Nebula, too. The video below shows you a close-up of the Veil Nebula taken with Hubble.